Metaphysics & Art: Universals & Particulars

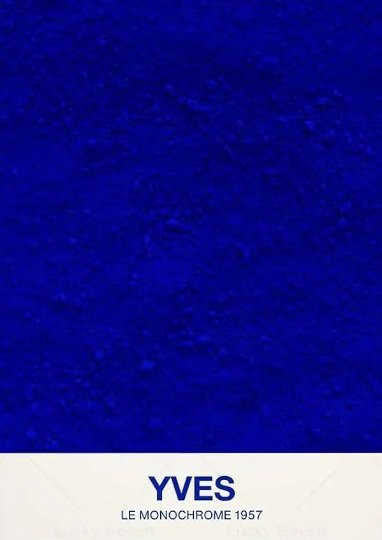

The philosophical debate between the distinction of universals and particulars centres on whether certain qualities exist independently of themselves or only as specific instances in individual objects. As a working artist the simplest way for me to illustrate this distinction is by utilising the collection “Monochrome: The Blue Epoch” by Yves Klein’s. The collection is famously known for eleven identical looking artworks all painted in a distinct blue called “International Klein Blue” which he patented in 1960.

Yves Klein Blue, 1957

Each of Klein’s monochrome paintings, although a particular artwork, is imbued with this same distinctive colour. From a realist perspective, Klein's works demonstrate the instantiation of a universal: the universal of his “IKB blueness". Even though each painting is a unique, particular object; differing in presentation, they all share the universal property of being blue and specifically the IKB blue. David Armstrong, argues that universals are ‘repeatable entities’ [1] that can exist in different locations at the same time. In Klein's artworks the colour IKB is incorporated in all the artworks. While these are different particulars, they all share the universal property of IKB. As Armstrong puts it, universals like the vivid blue properties of IKB ‘can be wholly present in multiple particulars at once’ [2]. In this way, the blue in each painting is the same universal property, even though it exists in all identical paintings in the collection.

Nominalists, by contrast, reject the existence of universals. They argue that only particulars exist and what we call ‘universals’ are merely linguistic conventions we use to group similar objects. A nominalist would view Klein’s various IKB paintings as all being particular paintings and individual artworks that we describe as "blue," but there is no actual abstract entity or universal "blueness" that exists beyond the individual paintings themselves. Nelson Goodman argues that resemblance between particulars is sufficient for our understanding of properties: ‘We call things similar not because they share a universal, but because we group them based on resemblance’ [3]. Therefore, Klein’s monochromes are grouped together as “blue” merely because we observe and categorise their similarities, not because they share an independent universal of “blueness”.

The debate between realism and nominalism becomes more nuanced when we consider Klein’s own intentions, the artist viewed colour not merely as a physical property but as a spiritual experience. From a realist perspective, this can be interpreted as Klein’s acknowledgment of the universal, transcendent nature of colour; an abstract entity that goes beyond a particular artwork. However, from a nominalist perspective, Klein’s work challenges the viewer to think about the role of language and perception in art. Interestingly, all eleven of Klein’s identical works were each priced differently to reflect their individuality. For Klein, while each painting visually looked the same, the impact each had on the buyer was completely unique,[4] provoking the viewer to contemplate the similarity and differences of experience across different particulars, without necessarily invoking an abstract universal.

Bibliography

Armstrong, D.M., Universals: An Opinionated Introduction (Boulder: Westview Press, 1989)

Goodman, N., Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1976)

Klein, Y., Yves Klein: Selected Writings (London: Tate Publishing, 2010)

Yves Klein, "Exhibitions – Yves Klein: Proposte Monocrome, Epoca Blu – Yves Klein." yvesklein.com. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

[1] Armstrong, Universals: An Opinionated Introduction, p. 29.

[2] Ibid., p. 36.

[3] Goodman, Languages of Art, p. 56.

[4] Klein, Yves Klein: Selected Writings, p. 12.